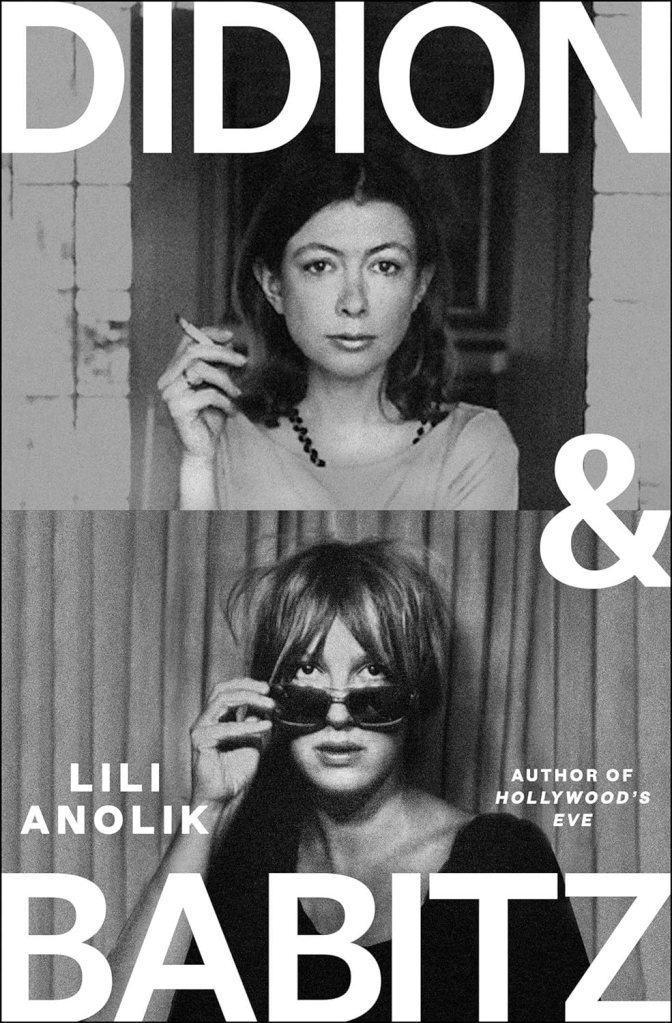

This is a book liable to dizzy readers with it’s Hollywood name drops- its namesakes, Harrison Ford, Jim Morrison, and Igor Stravinsky to name a few. Upon first glance it might look like just another docu-read on the infamous Didion, but no- this is Babitz’s book, her redemption. Initially it seems to pit Eve Babitz’s arc against Joan Didion’s, but by the end demonstrates the two women were unknowing mirrors of each other. Or perhaps knowingly, sprinkled with a mutual refusal to admit it. Translation: they were frenemies. What is also clear, author Lili Anolik had a favorite, and somehow she made me feel the same way.

As Anolik puts it, ‘Eve is Joan’s ideal self….the person Joan takes pains to present herself as in her writing…is the person Eve actually is.’ Joan was a machine as a writer, extremely disciplined and ambitious, and she siphoned the anarchic, drug-induced culture of the time through her circle of acquaintances as material for her novels. Eve however, lived it, she was her art (and an addict for a period of time). And regardless of the implication of her choices, i.e. posing nude for photographers, coked-out partying at the Chataeu, gay boyfriends, she knew how the strings were pulled in Hollywood and she would not suffer the illusion that she was anything less than the master puppeteer.

Eve began her career as a visual artist making album covers, most famously for Buffalo Springfield Again in 1967 (collage), Linda Ronstandt’s Heart Like a Wheel in 1974 (photo), and my personal favorite, Earth Opera’s self-named album in 1968 (collage). However, after a tragic comment from a lover during one of her painting sessions in late 1970 (Is that the blue you are using?) all outbound trains on the visual arts tracked ceased. For good.

Albeit painful, perhaps not so tragic, after all it was writing that coalesced all Eve’s passions, in particular order, Los Angeles, partying, and gossip. Her first book, Eve’s Hollywood, edited by Joan and her husband John Gregory Dunne, whom she called “terrifyling exacting,” jump started her literary career. Although it made no waves among critics or sales at the time, Eve was still finding herself published in Rolling Stone, Vogue, and Esquire, among others. Written a few years later, and widely considered Eve’s pièce de résistance, Slow Days, Fast Company, is where one is told to go to see Eve at her best.

The pace with which I finished this read surprised even myself. Beyond the complex relationship between the two women, the historical context of this book appeals to me. Although my physical container is 80s born, my soul seed belongs in the 1960s. It was a fascinating time, a conundrum with its juxtapositions. On one hand the late 1960’s and 1970s were a psychedelic, free-wheeling, liberated conflagration. Reckless decisions abounded. But on the other this was a generation that grew up with a wealth that this country had never seen previously in the 20th century. It was the post-WWII boom. Daddies were back home from war and slated to earn, weapons of war manufacturing transitioned to big boat Cadillacs and Buicks, plus suburbia and shopping malls were sprouting everywhere. Elitism, space, and privacy reigned.

But here in lies the point. The baby boomer generation was so wise and astute in their rebellious proclivities. Think of the restlessness that would underpin the entitlement of a young person who was handed everything. For example, as they transitioned to their ivory tower universities in the 60s (which exempted them from the draft) their education and access gave them the deeper cultural and historical context on the lingering and failing Vietnam War. Rightfully so, they made their voices known.

This rebellion is utterly apparent in Eve. The book details the plethora of opportunities she had to take advice from professional editors and writers to hone her craft, and sometimes her message, to make inroads into the literary establishment. Most of the time, it was for naught, partly due to laziness, partly due to Eve. She would not sacrifice her voice. And it wasn’t until much after her heyday in 2014 that the establishment acknowledged her: first Anolik’s 2014 Vanity Fair piece, then in the reissuing of Babitz’s books, there was the New York Public Library panel dedicated to Eve wherein icons like Jia Tolentino and Zosia Mamet participated, and in 2019 the New York Review Books Classics issued a new collection of some of Eve’s unfinished work (I Used to Be Charming). There was even a poster on the corner of Canal and Hudson in Manhattan of Eve’s Sex and Rage book in 2019. I beamed with happiness at her cultural applause, albeit a few decades late.

Although we didn’t need more proof that Eve’s life was poetry, as the book winds down we learn that the infamous lyric of one of her most torrid lovers, Morrison, is what ultimately ended Eve’s passionate partaking in public life. It was 1997 as Eve was leaving a family brunch, she was trying to light a Tiparillo cigar on her ride home and a match dropped to her skirt and lit her body on fire. Eve lost consciousness, suffered third degree burns on 50% of her body, and had a 50% chance of survival. But Eve survived, no question her constitution was cockroachian, but her life was never the same. She rarely left her apartment and her writing ceased. She passed in 2021, fittingly a mere six days before Joan.

What is important to note, especially to the incensed Joan fans, is that these were two very independent women, living in dependent times. Despite their tough exteriors, they both had their insecurities: the book notes several letters to publishers where both women were chomping at bit for approval. And I think its fair within the zeitgeist of the time that there were thorns to work out, i.e. how was the modern feminist archetype going to play out? As it turns out (political upheavals withstanding) we didn’t really have to chose. So for me, the negative takes on Joan in this book just make the titan a little bit more real. And the limelight that Eve receives is gratifying, especially given that the silence and ridicule she experienced was on the the part of men (many of whom were once her lovers). There is room in the pantheon of feminist literature is there not? This book, although at points winded, and Bridgerton-esque with its ‘Reader’ insertions, is an exercise in humanity if we look beyond the classic formula of pitting two female writers against each other.

Leave a comment